Latest updates first

Synopsis PRP Research to 2025

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) represents an increasingly explored autologous orthobiologic in the therapeutic landscape for osteoarthritis (OA). Derived from a patient’s own blood through a centrifugation process, PRP delivers a concentrated solution of platelets and an array of bioactive growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor (TGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).1 These components are believed to stimulate an immunological and inflammatory response that supports physiological healing, modulates inflammation, promotes tissue repair, and stimulates anabolic processes within chondrocytes, synoviocytes, and mesenchymal stem cells, with the overarching aim of alleviating pain and potentially slowing disease progression.1

Current evidence suggests that PRP injections, particularly leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP), can offer superior pain relief and functional improvement when compared to traditional treatments such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and corticosteroids. This benefit is most notable in patients with mild to moderate knee OA (Kellgren–Lawrence grades I–III).2 While some studies indicate sustained effects up to 12 months, it is important to note that the onset of pain relief with PRP may be slower than with corticosteroids.4 The effectiveness of PRP can also vary significantly depending on the specific joint affected.6

The safety profile of PRP is generally favorable, with reported adverse events typically mild and temporary, primarily consisting of post-injection pain.7 The autologous nature of PRP inherently minimizes the risk of immune reaction.10

Despite these promising outcomes, the exact clinical utility of PRP remains a subject of ongoing discussion and its specific applications in clinical practice are quite varied. A primary challenge lies in the substantial variability of preparation protocols, including differences in platelet concentration, leukocyte content, and activation status.1 This heterogeneity complicates consistent conclusions and reproducibility across studies and therefore requires individual clinicians to monitor their own results (ours shown below). Consequently, major clinical guidelines from prominent organizations such as the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) maintain cautious or inconclusive stances, citing insufficient evidence and concerns regarding study bias.2 Furthermore, current imaging studies do not demonstrate that PRP promotes cartilage regeneration or halts the structural progression of OA.2

This blog / post below summarises some important studies and some of our own patient reported outcomes with PRP therapy, with the more recent appearing first.

Update Late 2021

The PRP literature expands constantly, which is good because we all need more precise data. An important paper published in Arthroscopy July 2021 did a network meta analysis. Zhao et al. from Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine included 43 randomized controlled trials in patients with knee osteoarthritis (level II evidence -for more about evidence levels see here). They compared intra-articular hyaluronic acid (HA), leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma (LP-PRP), leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma (LR-PRP), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), adipose mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs), and saline (placebo) during 6 and 12 months of follow-up. During the 12-month follow-up, both AD-MSCs and LP-PRP showed pain relief effects and functional improvement was achieved with LP-PRP. “BM-MSCs seem to have potentially beneficial effects, but the wide credibility interval makes it impossible to draw a well-supported conclusion”. “HA viscosupplementation clinical efficacy was lower than that of biological agents during follow-up”. The authors concluded “Considering the evaluation of treatment-related AEs [adverse events], LP-PRP is the most advisable choice.”

In the related editorial Dr. Hohmann notes that Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) is the safest option, with the greatest effect on function and a good effect on pain, confirming the results of another recent network meta analysis (Migliorini et al. July 2020) that concluded: “Intra-articular injections of PRP demonstrated the best overall outcome compared to steroids, hyaluronic acid and placebo for patients with knee osteoarthrosis at 3, 6 and 12-months follow-up. Among CCS, hyaluronic acid and placebo, no discrepancies were detected.”

Migliorini et al. July 2020 also found that multiple RCTs (randomised clinical trials) found that multiple PRP injections resulted in significantly better outcomes than a single injection, something that is clear to me from administering PRP therapy.

Update Early 2021

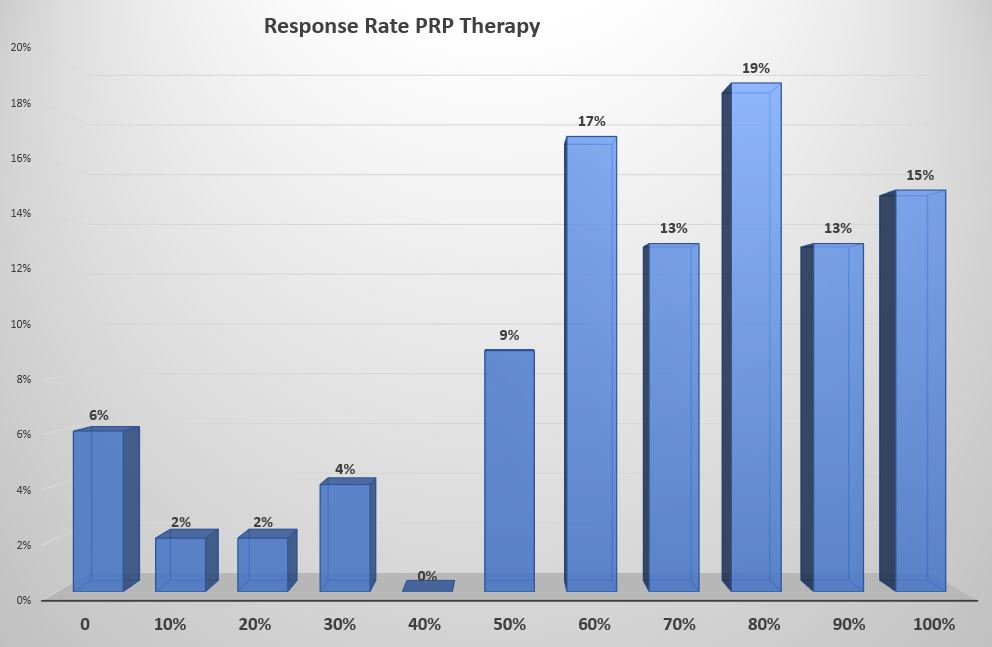

The following data was collected from ~60 patients who undertook PRP therapy in the latter half of 2020, and is based on our updated PRP protocol and includes both tendons and joints (but 80% were joints). As you can see 86% achieved a >50% improvement in pain levels when measured at more than 6 weeks post therapy. This correlates closely with an 85% satisfaction rate. These results are better than our earlier data. There may be a number of reasons for this: may indicate the higher mix of joint versus tendon problems, we may be treating less severe cases, and/or we may have improved our technique and protocols (we have changed several factors as we gain experience and learn more from others around the globe).

Update 2020

To see lots more information about PRP therapy go here.

There are a number of recent PRP studies that challenge the accepted dogma that corticosteroid injections are the first choice when conservative management fails. One such from Jane Fitzpatrick and colleagues (an Australian study -see here) showed that patients with chronic gluteal tendinopathy for more than 4 months achieved greater clinical improvement at 12 weeks when treated with a single PRP injection than those treated with a single corticosteroid injection.

Larry Miller and colleagues did a meta-analysis and found a total of 16 randomised controlled trials (18 groups) of PRP versus control for tendinopathy. They found that PRP was more efficacious than control in reducing tendinopathy pain, with an effect size of 0.47 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.72, p<0.001), signifying a moderate treatment effect. Heterogeneity among studies was moderate (I2=67%, p<0.001). In subgroup analysis and meta-regression, studies with a higher proportion of female patients were associated with greater treatment benefits with PRP.

They concluded that “injection of PRP is more efficacious than control injections in patients with symptomatic tendinopathy.”

Update September 2017

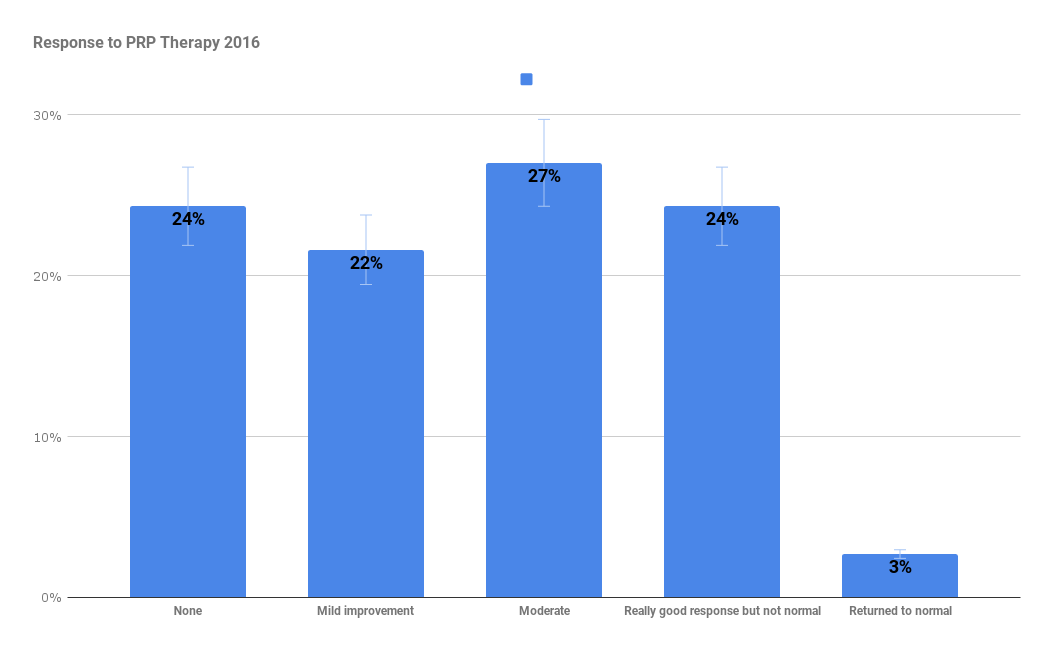

I have reviewed the data on 50 cases of PRP therapy (from 2015-2016) that fulfilled the above criteria. Thanks to those who responded to my emails. The data is shown below in graphical format. The responses are based on 4-6 month follow-up data. 55% had at least a moderate improvement with 27% an excellent response -remembering that virtually all these patients had failed all other therapies. Unfortunately 24% did not respond significantly. Most of these patients had plantar fascia, elbow tendon, or achilles tendon tears.

Update October 2015

PRP (platelet-rich plasma) therapies have been used for over a decade for a whole number of clinical problems (see PRP wikipedia entry). PRP is blood plasma that has been enriched with platelets and contains (and releases through degranulation) several different growth factors and other cytokines that stimulate healing of bone and soft tissue. It is a great concept but how should it be used? The research on PRP has suffered a common problem seen in clinical medicine. Researchers and clinicians have a new treatment/test/technology and hope to find a use but don’t know how to choose the right group of patients/problems/complaints/ or phenomena to test it with or which variables to manage/control. It is surprising that we make much headway as the constraints and variables are numerous.

In musculoskeletal medicine it has been used for many purposes but I will focus on its use in tendon injuries.

In the case of PRP therapy and tendon conditions there is little homogeneity between the studies. The evidence for PRP (platelet-rich plasma) therapy in tendinopathies is mixed and is summarized in the paper by Kaux et al in the JSRM[i]11. Overall the literature on PRP therapy is generally neutral or positive but the variables and study designs make it difficult to either refute or confidently endorse the use of PRP for a given clinical scenario.

If you look only at studies which were of level 1 evidence , had a followup period of at least 6 months and used ultrasound guidance (3 lateral epicondylitis studies, 2 rotator cuff (not including the study below), 3 patellar tendon) then there is substantial evidence that a subgroup of patients do very well with PRP.

In particular I have been impressed by the, as yet unpublished, study of Dr. Francesco Arrigoni at the University of L’Aquila, Italy, that was presented at RSNA Chicago in 2014, and later featured by auntminnie.com online. In a retrospective study of 240 patients they found that ultrasound-guided PRP injection of the supraspinatus tendon significantly outperformed the use of medical and physical therapy alone.

Arrigoni and colleagues evaluated the effectiveness of ultrasound-guided PRP injection (2 injections 21 days apart) of the supraspinatus tendon by comparing it with medical and physical therapy alone. Patients were included in the study if they had a diagnosis of tendinosis or small focal tear of the supraspinatus tendon (< 1 cm). They followed up all patients with MRI up to four years.

After 4 years the results are summarized in table 1:

| MRI Better | MRI same | MRI worse | Pain better | Function better | |

| PRP Rx | 32% | 48% | 20% | 75% | 56% |

| Physical Rx | 3% | 34% | 63% | 16% | 9% |

He acknowledged a number of limitations to the study. Patients were not divided by age, and the medical and physical therapy was not standardized. It should also be noted that they did not quantify the degree change of the tendinopathy on MRI and the medical therapy was not standardized.

Who are these PRP responders? It is not clear from the published studies as a whole, as the patient selection is highly variable and based on clinical features that almost certainly represent a variety of different pathologies. What is lateral epicondylitis or plantar fasciitis? The clinical syndromes are associated with a variety of imaging findings. The mechanisms of pain in any tendinopathy may be multiple it it seems likely that PRP is an appropriate treatment where the mechanism of pain is linked to a failure of healing associated with a tendon or (plantar) fascia tear*. Therefore if I can demonstrate this failure using ultrasound then it makes sense that this group of patients are potential responders. The first of my selection criteria involve persistent pain linked to an unhealed tear demonstrable on scanning (how one knows a tear is unhealed is the subject for another day and uses technology not yet available on standard ultrasound machines). From the literature and my own observations I have made the following conclusions to assist me in my own practice and so as to use PRP in a consistent and reproducible way (and hopefully deliver maximum benefit).

My criteria (2015) for selecting patients that may benefit from injection with PRP are as follows:

The patients should meet these clinical and scan criteria:

- Small unhealed partial thickness or split tears of the tendon confirmed with ultrasound or MRI and supported by ultrasound elastography where possible

- Symptomatic for > 6months

- Functional limitation

The PRP injection:

- Must have a platelet concentration 3-4 x blood

- Have small numbers of white cells

- Have no red cells

- Must not be directly mixed with local anaesthetic or corticosteroids

- Will be directed into the abnormal tendon with smallest gauge needle possible

The patients having PRP:

- Should avoid anti-inflammatories and aspirin from one week prior until three weeks after the injection

- Should rest the tendon for several days followed by an isometric strengthening program for the affected part

Ideally all patients treated should be followed up both with ultrasound and clinically as the evidence suggests the benefits are not immediate. The clinical trails often showed the biggest differences at 6-12 months and beyond post injection.

* For a complete review of treatment review of plantar fascia injection therapy evidence see here. Though not stated in the abstract the article states “PRP had the highest probability of being the best treatment [for plantar fasciitis] in the medium term.”

- Platelet-Rich Plasma for Osteoarthritis in 2024 – More Hype, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://www.sportsmed.org/membership/sports-medicine-update/spring-2024/platelet-rich-plasma-for-osteoarthritis-in-2024

- Platelet-Rich Plasma for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Comprehensive …, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12156035/

- Comparison of hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma in knee …, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40069655/

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections Are Inferior to Corticosteroid …, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40081606/

- Analyzing the performance of platelet-rich plasma and bone marrow aspirate concentrate injections for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis – Mayo Clinic, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/physical-medicine-rehabilitation/news/analyzing-the-performance-of-platelet-rich-plasma-and-bone-marrow-aspirate-concentrate-injections-for-the-treatment-of-knee-osteoarthritis/mqc-20578651

- (PDF) Efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials – ResearchGate, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371930900_Efficacy_and_safety_of_platelet-rich_plasma_injections_for_the_treatment_of_osteoarthritis_a_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis_of_randomized_controlled_trials

- Ultrasound-guided injection of platelet-rich plasma for …, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10072988/

- Platelet-rich plasma for rotator cuff tendinopathy: A systematic …, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0251111

- Comparison of hyaluronic acid and platelet-rich plasma in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review – PubMed, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40069655

- Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Treating Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports, accessed on June 30, 2025, https://jocr.co.in/wp/2025/03/01/effectiveness-of-platelet-rich-plasma-in-treating

- [i] Kaux JF, Drion P, Croisier JL, Crielaard: Tendinopathies and platelet-rich plasma (PRP): from pre-clinical experiments to therapeutic use. JSRM 2015; 11: 7-17.